Page 3

30-second board

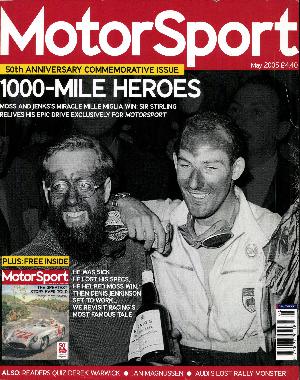

In the tracks of Nuvolari -- 123mph to Brescia Fifty years on from Stirling Moss's record-breaking Mille Miglia victory, this…

In the tracks of Nuvolari -- 123mph to Brescia Fifty years on from Stirling Moss's record-breaking Mille Miglia victory, this…

Moss still boss 'It strikes me how little Stirling Moss has changed from the sparky 25-year-old who won the 1955…

World Champions put their weight behind F1s 'seniors tour' Four-time World Champion Alain Prost has committed to the pilot Grand…

Formula Fiat Abarth, Mugello, 1980 There were so many question marks over my first car race, because in those days…

Rally legends and ground-breaking rally cars will thrill the crowds on a purpose-built gravel special stage during the 2005 Goodwood…

Alain Prost had his first car races on asphalt since his 1993 World Championship-winning season when he contested the French…

Resembling an escapee from a Russ Meyer exploitation epic, Linda Vaughn remains the greatest trophy queen of them all. This…

David Coulthard moved to the head of the table of British points scorers in the Formula One World Championship thanks…

Le Mans bid boosted by big win in Florida endure. Elated Aston Martin squad celebrate first international success for marque…

John Tojeiro This renowned chassis designer died on Wednesday, March 16. He was 81. Born in Estoril to a British…

David Clark gave his ex-Chris Amon Elva victory in its first race for 38 years, while Neil Fowler and Steve…

By the end of 1973 Mark Donohue had achieved most of his goals in motor racing. Since 1967 he had…

Citicorp Can-Am Challenge, St Jovite, June 9, 1977 It was meant to rekindle past glories, but the first round of…

1974 Belgian GP at Welles How did you land the Brabham drive? I was having a lot of success in…

1976 Swedish Rally by Per Eklund What was the main opposition ? Well, there were three Lancia Stratos. Björn Waldegård…

1985 -- Porsche plays a waiting game lckx and Mass win Silverstone 1000Km after Lancia's double charge falters For more…

Sympathy for Ferrari over its stand on test cuts is thin on the ground for good reason The growing division…

Banished from the Principality in 1998 when Formula 3000 'hijacked' its Monaco GP support slot, Formula Three gets its prestige…

Vintage American Road Racing Cars 1950-1970 by Harold Pace & Mark Brinker, ISBN 0 76031783 6, published by Motorbooks International.…

Frisco surprise Sir, I live one mile from San Francisco's Golden Gate Park and a drive through the park is…

Formula 1 continues esports push with second season The second season of the Formula 1 esports season will begin in April, with players offered the chance to be a part…

Crunch the numbers and the future looks bright for Alfa Romeo, Racing Point and Toro Rosso, but is time running out for Ferrari? Image: Motorsport Images A graph can explain…

US racing category nominee #7: Parnelli Jones Legends - Parnelli Jones Vol 75 No.4– April 1999 Jones was a boyhood hero of mine. I became aware of him in the…

This week in motor sport from the Archive and Database, with Formula 1 in Japan, South Africa, Vegas and Mexico, and Senna and Prost coming to blows on track. October…