For the next year’s Tasman races Chris bought a later Cooper, and regularly qualified ahead of several of the visitors. Parnell was there again, running the Bowmaker Lolas, and he took Chris aside. “He told me I’d better get a passport. Months later he called me and said he wanted me in London for Easter – four days later! Apart from a few races in Australia I’d never been out of New Zealand. I’d never even seen a jet plane. I got to Heathrow on Good Friday. Reg’s secretary, Gillian Harris, took me to the Parnell workshop in Hounslow for a seat fitting in an F1 Lola. I spent the night in a hotel, and next morning Reg took me to Goodwood for official practice for the Easter Monday F1 race. I couldn’t believe how little power those 1.5-litre F1 cars had. No torque either. I had to change my driving style completely. But I was fifth in the race. It was the first F1 race I’d seen, and I was in it.”

His first World Championship race was at Spa, no less. On a damp track he held a remarkable sixth place before an oil leak put him out. He quickly settled into the little Parnell team: “I used to go to the workshop every day, just to potter around, because the mechanics wouldn’t let me touch anything important. There was a caff in Hounslow near the workshop where you could have a three-course lunch, real English stodge, for one-and-six.”

Chris was seventh at Reims and Silverstone, then crashed at the Nürburgring when his steering broke. He was unhurt, but more serious was his accident at Monza five weeks later. “I’d never been there, obviously, and this was the last time they tried to use the combined banking and road circuit for the Italian GP. In practice so many cars broke on the rough surface that they decided to run on the road circuit alone. I went off at Lesmo, cartwheeled into the trees and was thrown out. I had broken ribs and concussion, and I was in hospital for several weeks.

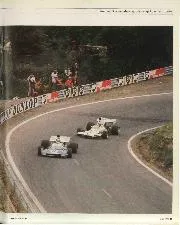

Frustrated by a Matra puncture, Amon impressed with a record-breaking drive in the 1972 French GP

Motorsport Images

“Reg was a no-nonsense guy, almost like a father to me. F1 was very friendly then. I was just the young newcomer, but everyone made me feel welcome: none of the back-biting there must be today. You could talk to anyone, from the World Champion down. Being steeped in motor racing history, I found myself surrounded by people I’d grown up almost worshipping. I wondered what on earth I was doing there.

“For 1964 Reg had big plans: monocoque Lotus 25s for Mike Hailwood and me, and the latest Climax V8s. Then he got appendicitis, wouldn’t go to the doctor – he was stubborn – and by the time they got him to hospital it was too late. He was only 52. His son Tim had to pick up everything. He did his best, but the heart went out of the team. We did 1964 with Lotus 25s, which were good – night and day compared to the Lolas – but we ended up with customer BRM engines, which weren’t so good. Although Mike was pretty much paying for his drive, Tim was struggling for budget. We’d buy second-hand gearbox spares from Lotus, so when you got a rebuilt gearbox it was already tired.

“I’d been living in a bedsit in Surbiton, but now I moved into the famous flat in Ditton Road, Kingston, with Mike Hailwood and Peter Revson. The stories about that place have become exaggerated down the years, but some extraordinary things did go on. My friend Bruce Harré, who’d come over from New Zealand to work at McLaren, stayed there too, and off and on so did Tony Maggs and Howden Ganley.

“There were three bedrooms, so we moved around depending on who was doing what and to whom with lady visitors. There was a crashed Cooper chassis propped up in the hall, which somebody was always going to ship back to New Zealand. It was there for months. The poor unfortunate who lived downstairs was a sitting tenant, not paying much rent, and the landlady had wanted to get rid of him for years. The police were always coming round because of complaints about the noise. They’d come in, turn the music down, have a couple of beers and then leave us to it. In the end the man downstairs moved out, so the landlady got her wish.

“I had my 21st birthday party the day after the 1964 British GP, and just about the entire F1 grid came. BP were making a film about Mike Hailwood and wanted to show him relaxing, so they said they’d foot the bill if we let a film crew in. But the crew got so plastered they were incapable of doing any filming. BP had to pay for another party and and do it all again.

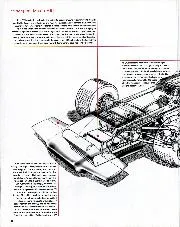

March failed to deliver on promise for 1970

Motorsport Images

“Ulf Norinder asked me to share his Ferrari GTO in the Reims 12 Hours. Just before the race he sent me a telegram, saying he had to go to a wedding – his own! – and would I find another co-driver. So I called this promising young F3 racer, J Stewart. We duly found the Ferrari in the Reims paddock with a rather disgruntled mechanic. Luckily Bruce Harré had come with me for the ride. In practice it did a piston: there was no spare engine, of course, no spares even, and Ulf’s mechanic started to pack up. He was reckoning without Harré, who said, ‘Hang on, let’s pull the engine out and rebuild it.’ The New Zealander approach, you see.

“Bruce tore it apart – he’d never seen the inside of a Ferrari engine – and it hadn’t done a great deal of damage, just the piston, a couple of valves, a few other things. Bruce went over to the factory Ferrari guys, who were there with Surtees and Bandini and co. They rummaged around in their truck and came up with some bits, and he rebuilt it in the paddock. By now the mechanic had gone off in a huff. During the race we needed some new brake pads, but they were in the boot of the mechanic’s car and no-one could find him. Later on we were having a tyre change and could only find one rear tyre. It was a while before we twigged that we’d been racing with the other one in the back of the Ferrari. But the engine Bruce rebuilt never missed a beat, and we finished.

“For 1965 Bruce McLaren hired me. He was running the first McLaren sports cars and doing a lot of tyre testing for Firestone, which pretty much financed his operation. As he got busier I took over most of the tyre testing. I did thousands of miles at Goodwood, Silverstone, Snetterton, Brands, even Zandvoort. It was great experience, and with the Group 7 McLarens I was dealing with proper horsepower. In an average day I’d do at least 300 miles. You have to be flat out all day, because if you’re not on the limit you don’t learn anything. I found I was quite sensitive to a car’s behaviour on different tyres and settings, and could feed it all back to the tyre guys.”

At Le Mans Chris shared a 7-litre Ford MkII with Phil Hill. “We had a big speed advantage over the Ferraris, but our gearboxes were weak, and all the Fords retired. After that they got Pete Weisman involved and ended up with a really strong transmission.” In an F2 Lola he won the Solitude Grand Prix, and six days later he won the Martini Trophy in a McLaren from the back of the grid, standing in for Bruce who’d been burned by a petrol fire in practice. Two days after that, back with the daily grind of tyre testing at Brands, the McLaren’s rear suspension broke and it turned sharp right into the bank. “I was flat in fourth on the back of the long circuit. It was like an aircraft accident, bits spread for 200 yards, with me still in the seat. I was a bit knocked about, so they decided to take me to hospital. The ambulance wouldn’t start and they had to give it a tow.” Three days later, nursing his bruises, he was off to the Nürburgring to drive a Parnell Lotus-BRM in the German GP.

Scoring a famous win for Ford with Bruce McLaren at Le Mans in 1966

Motorsport Images

Chris ran as team-mate to Bruce McLaren in Group 7 races in the UK in 1966 and in the inaugural Can-Am Series, but the big event that year was Le Mans, where they scored a famous win for Ford. “All the works Fords were on Goodyears except ours: we were contracted to Firestone. In the wet and dry conditions the intermediate Firestones were terrible, and kept chunking. By Saturday evening we’d had two extra pitstops and were three laps behind the leaders, and Bruce said, ‘I’m going to sort this out.’ He went to the Firestone people and said, ‘We’re either going to withdraw the car, or we’re going to put Goodyears on it.’ So Firestone said, ‘Put the Goodyears on.’ They called me in, changed the tyres, and Bruce shouted to me, ‘We’ve got nothing to lose. Just go like hell.’