Delusion

It was going to be such a good race, we thought. The break after the United States GP and the Brazilian GP would mean that everyone could get themselves sorted out and repair any damage, and put right any early season faults. Many new cars were completed and much testing done, particularly on the Imola circuit, so that we could really view the San Marino Grand Prix as the true start of 1990.

The Tyrrell team produced their new cars, the 019 models, Benetton produced their B190 models, the resurrected Brabham team their BT59 cars, Minardi their new M190 cars and it all seemed to be building up into a fine start to the European season. McLaren and Honda had been fine-tuning the MP4/5B with engine characteristics adjusted for the high-speed, hard-working, conditions of the Imola circuit, and Renault had put in a lot of work on the RS2 engines. Much was expected from Ferrari, the Imola circuit effectively being their home ground, and there was talk about a new version of the V12 engine, together with new bodywork aerodynamics and there was an electric air about the place as the teams began to assemble for the third round of the 1990 season.

The Italian racing enthusiasts didn’t miss a moment of it all, and were there in their thousands ready for practice and qualifying to begin on Friday morning. For those who were up extra early there was the hour devoted to pre-qualifying in which the really ‘low-score’ teams from last year’s races had to fight among themselves for four places allowed for participation in the official practice and qualifying that was due to start at 10am Those involved were Olivier Grouillard with the lone OsellaCosworth, Tarquini and Dalmas with the new AGS JH25 cars, Bernard and Suzuki with Gerard Larousse’s Lamborghini powered Lolas, Gachot with the lone Coloni powered by Carlo Chiti’s flat 12 engine paid for by Subaru, the EuroBrun-Judds of Moreno and Langes, and the unusual inverted-broad-arrow 12 cylinder Life car, driven by Bruno Giacomelli. Nine drivers had to compete for four places all within the space of one hour, and even the four fastest were not guaranteed a race, merely the opportunity to try and qualify for the starting grid against all the successful people.

Ayrton Senna leads Thierry Boutsen and Gerhard Berger

Motorsport Images

Before pre-qualifying began the numbers were down to eight, for Dalmas had to be withdrawn as his injuries acquired during a testing accident the previous week had not healed sufficiently. When the other AGS failed to start and Tarquini was side-lined we were down to seven.

One very slow and faultering lap by the 12-cylinder Life project put paid to any hopes Giacomelli may have had about making a comeback, so we were down to six. It was very quickly obvious that the Lola-Lamborghinis should not really have to suffer the ignominy of pre-qualifying and Eric Bernard and Aguri Suzuki were assured of places in official practice. Grouillard and Moreno annexed the remaining two places, which was reasonable enough, so come 10am on Friday and we had a full complement of thirty cars and drivers ready for the serious business of the day.

The huge crowd were expectant and the sheer sound of Mansell leaving the Ferrari pits was enough to guarantee pole position. You did not need to see the red Ferrari getting on with the job, the sound was enough, but sound alone is not enough for the Longines-Olivetti automatic timing system and the read-out screens told the cold truth. The Ferraris were quick, but not as quick as they had been reported to have been in testing and the Honda-powered McLarens of Senna and Berger could not be ignored. There had been a moment of consternation in the Woking camp when Berger had to abandon his car just short of the pits, when the engine died, and run up the pit lane to get the T-car prepared for his use.

The morning had been warm and it continued that way, though a bit hazy when qualifying began at 1pm. Senna staked his first claim for pole position quite early on, and Jean Alesi whipped the new Tyrrell round in an impressive fashion to keep his name up near the top of the list for quite a long while. With very little fuss the Williams team and Renault were getting on with the job, and Riccardo Patrese soon staked an admirable claim for a leading position, not quick enough for pole position but quick enough to end the session in a select group of three drivers who got below 1 min 25 seconds, the other two being without surprise the two McLaren drivers.

Senna’s abandoned McLaren after retiring from the race

Motorsport Images

Just as conditions had reached something of a fever pitch and the top drivers were preparing to make their second attempts there was an ominous hush as the red flag indicated the cessation of qualifying. Pierluigi Martini had gone off the road and into the barriers in the new Minardi and though not seriously injured, was trapped in the wreckage and it was taking the medics a long time to extract him. By the time this was sorted out and Martini was off to hospital with a broken ankle bone, the delay had broken the rhythm of qualifying and it fizzled out rather inconclusively. Berger was just ahead of Senna, Patrese was third, Mansell fourth, Boutsen fifth and Prost sixth and the two McLaren drivers were both two whole seconds faster than the reigning World Champion with Ferrari’s best material.The air of disbelief among the tifosi was self-evident; not only were they deluded, they were cheated, for all the pre-race newspaper excitement had more or less promised that the Ferraris were going to anhilate the opposition, and it hadn’t happened. Alesi’s speed with Tyrrell 019 with its unusual aerodynamics around the nose area, was causing some head scratching for not only was the young French driver quick on lap times, indicating good driving round swerves, but his Hart-tuned Cosworth DFR engine was propelling the Tyrrell as fast as the Ford factory supported EXP engines in the Benettons.

Saturday morning was again warm and comfortable and the considerable crowds poured back into the circuit, hope forever springing eternally, but once more they were cheated or deluded, for the Ferrari engineers seemed to lose their way completely and the drivers were beginning to lose faith. Basically the McLaren-Honda team were surviving the odd bit of trouble and setting the standards, but they could not relax, for the moment they did Patrese and the Williams-Renault were in amongst them. Those people who were wondering why Ferrari were not challenging as had been promised almost overlooked the Williams team. Equally it was easy to overlook the performances of Alesi and the Tyrrell until you looked at the official time-sheets. At the end of the Saturday morning test session the blue and white Tyrrell was in third place, right in amongst the V10 Renault-engined cars, the V10 Honda-engined cars, and ahead of both V12 Ferraris, which took a lot of explaining.

Jean Alesi leads the Benetton and Lotus drivers

Motorsport Images

The four Lamborghini-powered cars, two Lotuses and two Lolas, never really saw which way the quiet young French driver, of Sicilian origins, had gone. The Tyrrell number two driver, with an identical car was just not in the picture, qualifying down towards the back of the grid.

The final qualifying hour had been forced to start twenty-eight minutes late, due to a delay in the morning when Moreno crashed a EuroBrun, but it did not affect the outcome. Getting below 1 min 25 secs was still the aim, and Patrese did an excellent 1 min 24.444secs, but then Berger set new standards with a 1 min 23.781secs which lasted only until Senna went out for his final run on the best sticky tyres that Goodyear could supply and did a shattering 1 min 23.220 secs and afterwards admitted that if he had been prepared to throw caution to the winds he was sure he could have reduced it to 1 min 23 secs nett; and who is to argue with him?

While Patrese could not match the Honda-powered pair there was no disgrace in that, and he was comfortably ahead of everyone else. The two Ferraris could almost be classed as ‘hopeless’ still being nearly two seconds off the McLaren pace, and Alesi was still right on their tails and an embarrassment to the Benefton and Lotus teams.

By the end of the day the Arrows team crept quietly away, neither Michele Alboreto nor Alex Caffi being quick enough to make the grid, and it cannot have been due to lack of driving ability, while young David Brabham failed to make the grid on his debut with the revitalised Brabham team now in Japanese ownership. With Martini being withdrawn from the list following his accident it meant that his team-mate Paola BariIla was able to start in the second Minardi and only three drivers were officially not qualified. A ray of hope shone through from the turquoise-coloured cars that used to be called March and are now called Leyton House after their new Japanese owner, for Gugelmin qualified a respectable twelfth after both cars had failed to qualify in the iirevious Grand Prix. Once again the huge crowds of spectators had dispersed with nothing to rejoice about for they had been promised that World Champion Alain Prost and the hard-charging Nigel Mansell in the red cars from Maranello were going to crush everyone, and here they were nearly crushed by a new young driver with an Italian sounding name driving a Tyrrell!

Nigel Mansell leads Riccardo Patrese

Motorsport Images

Surprisingly they all came back on Sunday morning, sure once more that all would be well, but by mid-afternoon they knew once more that they had suffered Il grande illusioni. People who were desparately looking for ways of upsetting the very unsatisfactory apple-cart prophesied rain, but it did not materialise and race day stayed fine and dry, if somewhat overcast at times.

The “warm-up” half hour on Sunday morning saw Mansell raise the hopes of Ferrari fans, when he got his red car between the red and white ones of Senna and Berger, but it was only a warm-up test session. But such demonstration of faith by the Englishman brought forth appreciative cheers, even though fifth and sixth positions on the grid were not exactly promising, with the two McLaren-Hondas at the front.

The tension before the start was building up, in spite of all the gloomy signs, for somehow there is nothing to replace an actual race and the moment when all twenty-six cars set off together creates an entirely different situation to anything that has gone before. In the opening lap Boutsen got his Williams between the two McLarens, but Senna was already in a commanding lead. Patrese was fourth and unbelievably Tyrrell number 4 was in fifth place, ahead of both Ferraris. Yes, it was that young lad Alesi again, unabashed by Champions or Ferraris.

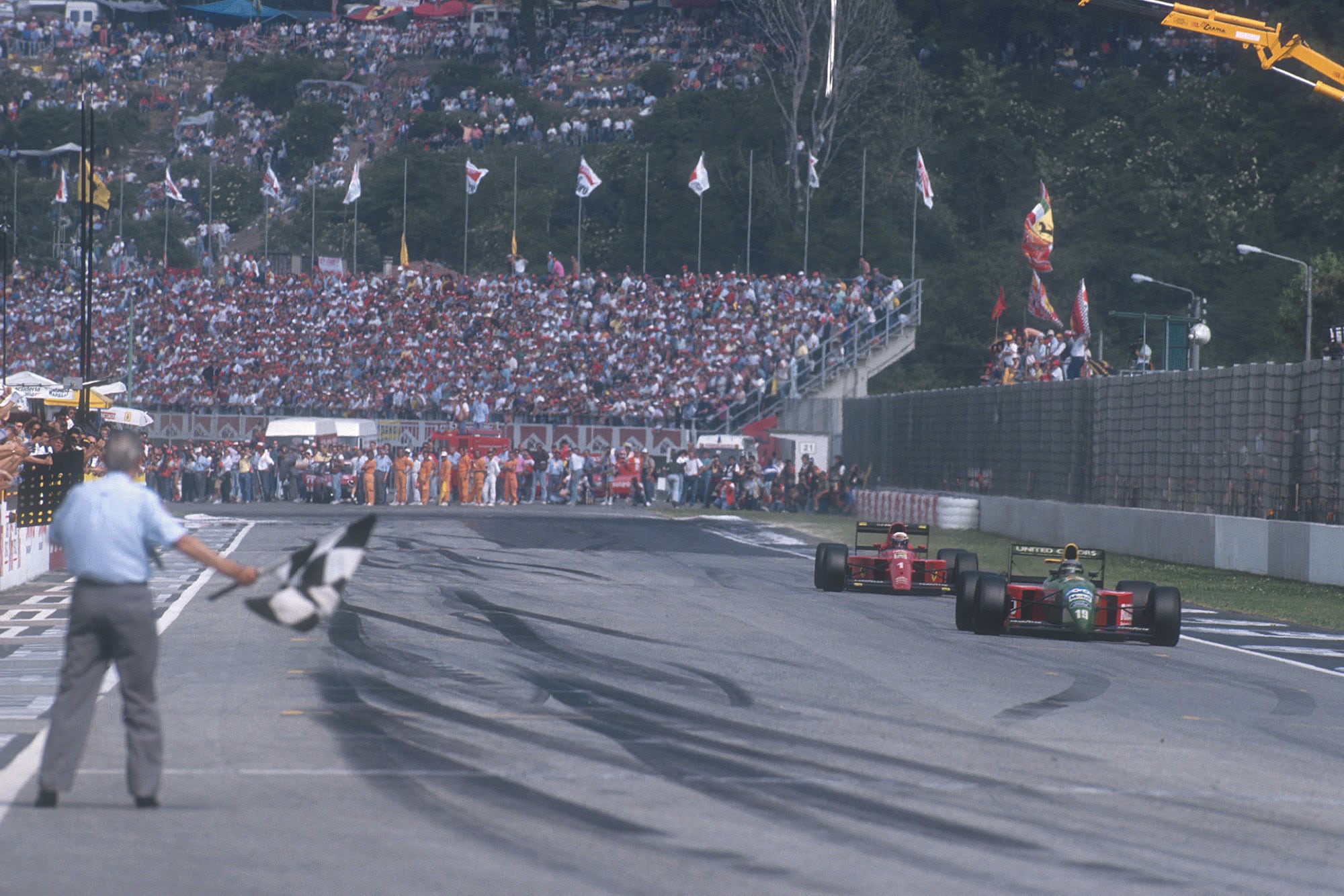

Nannini beats Prost to the line

Motorsport Images

Before the race had a chance to settle down there were screams of delight from the crowds as Senna was seen to be in difficulties; a rear wheel had broken up, the tyre had deflated and the rear brakes were inoperative as he sped down the hill to the Rivazza corners. After momentarily locking up the front brakes in a desperate effort to knock off some speed Senna had no choice but to steer clear of the following cars and run off onto the sand trap and subside out of the race. This was on lap 4 and it left Boutsen in the lead with Berger in second place suddenly conscious of his responsibilities now that his team leader had gone. Almost unnoticed the Ferrari drivers had regained their composure and disposed of the cheeky Alesi and a few laps later Nannini and Piquet rearranged the status quo by forcing their way past the Tyrrell with their works Cosworth powered-Benettons. With Senna gone so early it really was anybody’s race and for a time looked to be Boutsen’s but his Williams was playing up in the gearbox department, particularly in second and third gears. When it selected a lower gear instead of a higher gear without warning, the engine suffered from overrevving and that was the end of the Belgian’s hopes. As the Williams peeled off into the pit lane Berger found himself in the lead, much to the relief of the McLaren-Honda team. However, the Williams-Renault team were very happy with their assessment of the way the second car was going, and equally Patrese was pretty happy with the situation, even succumbing to pressure from Mansell who charged his way by into second place. Patrese still held a very confident third place, knowing his car was going splendidly and would have something in reserve for putting pressure later in the race.

Mansell was driving in a pretty ragged fashion, spending a lot of time on the grass verges and avoiding slower cars in a rather spectacular fashion, but nonetheless having a real go at things, unlike his team-mate who seemed to be out for a quiet Sunday afternoon drive, stopping to change tyres before half-distance as a first lap scuffle had caused him to put ‘flat spots’ on the front ones. Mansell’s heroics came to an end when he free-wheeled into the pits at the end of lap 39, the engine having cried ‘enough’.

Patrese celebrates his victory on the podium

Motorsport Images

All this time Berger was leading, but it was ominous that he was not drawing away from his pursuers, and when Patrese began to put on a bit of pressure once Mansell was out of the way, the Austrian driver seemed unwilling, or unable to respond. Patrese was now revelling in the fact that his car was running perfectly and was well able to stand some harder use in the closing stages, when others might be getting low on braking power, or having concern about tyre wear or fuel consumption. On lap 51 Patrese took the lead from Berger with relative ease, there being no sign of the Austrian putting up a fight, and his condition after the race suggested he had been physically incapable. Meanwhile, in third place Nannini was coming under pressure from Prost, but was fighting back valiantly and though the Ferrari claimed third place for a fleeting moment the Benetton was soon back in front again. So the race ran out its 61 laps, with Patrese determined not to make any mistakes and throw this race away. Berger followed him home into a far from satisfactory second place, with a very happy Nannini in third place with the new Benetton although Prost was perilously close behind him as they crossed the finishing line. Then came Piquet in fifth place in the second Benefton after a consistent but unexciting run, followed by Alesi in sixth place earning excellent marks for the new-look Tyrrell team. Just before the start Alesi had been forced to change to a spare car, and a third of the way through the race he had made an unscheduled decision to stop for a new set of Pirelli tyres. This had dropped him down to ninth place, but he soon fought his way back up to sixth, passing Warwick and Donnelly in the Lotus-Lamborghinis as he did so.

It wasn’t the race anyone had expected to see, but the end result gave a lot of people a lot of pleasure, especially the Renault engine people who have quietly worked away on their RS2 version of the V10, confident that its performance does not lack much from the V10 Honda. On the other hand Ferrari were perhaps over confident in believing that their V12 was more powerful than the opposition. When it proved not to be it threw the team into some confusion with the result that they got themselves in a muddle over suspension and aerodynamic settings and lost faith in their own bodywork changes.

That three out of the four V12 Lamborghini engines survived was something of a major triumph for Mauro Forghieri who designed the engine with Chrysler backing, but it still has a long way to go before becoming a race-winning engine. DSJ