1970 Belgian Grand Prix race report: Rodriguez reaps rewards

BRM’s persistence pays as they finally break the Cosworth monopoly through a Pedro Rodriguez victory; McLaren withdrawn after death of team leader Bruce

Pedro Rodriguez took BRM's first race victory for four years at Spa

Motorsport Images

When the Grand Prix circus assembled in the paddock at Francorchamps on Friday, June 5th, for the first practice session there was a very noticeable gap in the ranks. The orange cars of the Bruce McLaren Motor Racing Team had been withdrawn, for on the Tuesday previous McLaren had died in a crash at Goodwood, while testing his latest Can-Am racing car.

Qualifying

Practice was from 5pm to 7pm, and though a little light drizzle during the afternoon had some people in a nervous twitch, by the time the practice started everything was dry and the sun was shining strongly, so that the wonderful Francorchamps circuit was in superb condition.

As a sop to certain Grand Prix drivers the course had been modified slightly since the recent 1,000-kilometre sports-car race, and instead of taking the very fast Malmedy right-hand sweep at around 150mph, it was now necessary to brake really hard, going left of the grass island and then turning sharp right and joining the Masta straight on a left-hand sweep. This so-called chicane increased lap times to the order of seven to ten seconds, so a new set of standards for Grand Prix cars at Francorchamps was to be set.

For the record the fastest Grand Prix lap in a race stood to Surtees with the V12 Honda in 1968, at 3min 30.5sec, the fastest GP lap ever to Clark in a Lotus 49 in 1967 practice, at 3min 28.1sec and the fastest lap, regardless, to Rodriguez in a Porsche 917 sports car in 3min 16.5sec, 160.3mph. It will be recalled that no Grand Prix was held at Francorchamps in 1969.

Apart from the very sad absence of the McLaren team, which included Gethin who was to have temporarily taken Hulme’s place, and de Adamich with the Alfa Romeo-engined McLaren, there were other non-arrivals, these being Eaton with the third of the Type 153 BRM cars, the second Tyrrell entry, for Servoz-Gavin suddenly decided he had raced enough and opted out of the team, Moser with his “standard British Grand Prix Car Kit” built in Italy for him by Bellasi and Surtees with his private McLaren.

This left 18 runners, the last one being Soler-Roig, who was waiting for Lotus to finish modifying their second Type 72, so for the first practice there were 17 entries and for a time they all had to feel their way round the new, sharp Malmedy corner, it being interesting as it called for very heavy braking on the left-hand curve at the exit from the very fast Burnenvillle curve.

Stewart had two Tyrrell March cars to use, 701/2 as his mainstay and 701/7 as a training car, and he used the second one for settling in to the circuit before going out in the first car to establish any serious times. The works March cars were being experimented with as it was the first time they had been run at such high speeds and it was a matter of balancing the drag of the aerodynamic devices (the nose fins, the side tanks and the tail aerofoil) to maximum speed consistent with stability, and as most of the downthrust is directed to keeping the front down this was proving a tricky problem.

Jackie Stewart took pole in his Tyrrell – March

Motorsport Images

Amon’s usual car, 701/1, had undergone a complete rebuild, even to the extent of having a new monocoque, but like the axe that took off the head of Anne Boleyn, it was still the original, even though it had had four new heads and six new handles! Siffert was in 701/5 and neither of them put in a great deal of practice due to various adjustments being made and fuel feed experiments being carried out, for at Spa the cars spend a lot of time in a nose-down attitude on full throttle, which encourages the fuel to slosh forwards in the system rather than backwards, where it is needed.

The Brabham team was also experimenting with fuel systems and had pannier tanks on each side of the cockpit, as engines are always thirsty at Spa. The system of plastic pipes and electric pumps was a real “plumber’s nightmare”, but seemed to work. Brabham was in BT33/2 and Stommelen, as usual, was in BT33/1.

Team Lotus had a modified Type 72 for Rindt to drive, this being 72/1 which had rearranged rear suspension geometry that no longer had the much-vaunted anti-squat characteristics, but the car did not get very far, for after a few laps a rear hub seized up and broke the lower wishbone mounting away. Someone had not drilled an 1/8in breather hole in the hub upright casting on the right rear, and pressure build-up from heat blew out the oil seal the lubricant escaped, the bearing seized solid and the sudden reverse torque was more than the suspension had been designed to carry, for with inboard breather hole in the hub upright casting on the right rear, and was happening Miles was circulating in a Lotus 49C, making his first appearance at Francorchamps, having been over the previous weekend in an Elan to learn the way round.

Soler-Roig was awaiting 72/2, the second of the 1970 cars which had been modified very extensively. The monocoque had been taken apart, bulkheads were riveted inside the fuel tank spaces, half-way along, two bag tanks were now used on each side, with a filler on the left to fill the front ones, the inner cockpit skin had been strengthened and the rear surface of the cockpit had been moved forward to give a thicker box-section around the driver’s shoulders. All this had been done to improve the torsional stiffness of the monocoque, which had been part of the high-speed cornering instability. As on 72/1 the rear suspension had been altered to remove the anti-squat characteristics and on 72/2 an entirely new front suspension frame had been made removing all anti-dive characteristics. In consequence of all the work one could say that 72/1 had been modified to a 72B and 72/2 to a 72C.

“Hill was running without front fins or rear aerofoil, endeavouring to gain more down the straights by reduced drag than he was losing on the corners”

After Miles had done a bit of practice in the 49C it was given to Rindt, as he had not even started to record decent times with the Lotus 72. Graham Hill was going round and round in Walker’s rebuilt Lotus 49C, running without front fins or rear aerofoil, endeavouring to gain more down the straights by reduced drag than he was losing on the corners by loss of downthrust, but the results were not very conclusive.

Ferrari were also trying this dodge on the car Ickx was driving, but soon reverted to fins and aerofoil as Ickx found the car much too sensitive and twitchy without its aerodynamic downthrust aids, though this could have been because the suspension and tyres had been designed for high downthrust.

The BRM team were not at all happy as their gearboxes were giving trouble with the selectors not selecting properly and with gears coming out of engagement, though as they were BRM designed and built gearboxes rather than the ubiquitous Hewland boxes, they had to sort out their own problems.

Matra were busy changing ratios on their Hewland gearboxes, so did not do too much running, but when they did the French V12-cylinder engines sounded beautifully crisp. Colin Crabbe’s yellow and brown March 701 which Peterson was driving had been geared for an optimistic maximum of 195mph, so when it would not reach peak rpm in top the Swede left it in 4th gear, rather than waste time having the ratios changed, for it was his first race at Spa and he had plenty to learn. He was driving very smoothly and very confidently, and not all that slowly, his times being in the 3min 40sec, less than ten seconds slower than the Stewarts and Brabhams, which was very good for a first time out.

Ferrari had entered two cars and the second one was being driven by Giunti, who had the advantage of having driven a 5-litre sports car in the 1,000-kilometre race, so he knew what Spa was all about, and merely had to adapt himself to a single-seater and getting the most out of a lower-powered engine than he had been used to.

Courage was using the number three De Tomaso car, and waiting for a brand-new one to arrive from Modena. Like Amon’s March it was to retain the number 38/2, being a 100% rebuild of the second car, with the addition of wider rear track and different suspension geometry for the De Tomaso designer is still learning about high-speed single-seaters. Towards the end of the practice session the pace began to speed up a bit as drivers got used to the circuit and the evening began to get cool.

Brabham was trying really hard, as was Stewart, while Stommelen was driving impressively, and it looked as though the Scot was going to hold fastest time with 3min 31.8sec, not quite down to the old 1968 record, but as usual anyone who thought that reckoned without Brabham. As the Director of the race was preparing to end practice the swarthy Australian did a sort of Fangio act and pipped Stewart’s time, with 3min 31.5sec, just as practice finished.

Saturday was another glorious day and practice was from 2pm until 3:30pm, the two BRM drivers being out very smartly, as they had not really got under way the day before. Stewart was once more playing himself in with the spare Tyrrell March and Ferrari produced two cars for Ickx, 001 and 003, while Giunti was still driving 002, this being yet another 100% rebuild round a basic number, as 002 was the car that was crashed and burnt out in Spain.

Team Lotus had repaired the 72 and given it permanently to Miles, and Rindt had taken over the old 49C. The latest 72 had arrived but was being finished off so Soler-Roig still did not get a drive. Brabham was playing about with fuel systems and things and generally messing about so that he got in no fast laps at all, whereas Stewart with his two cars was well organised and after some practice with the spare car he went out in 701/2 and got down to 3min 28.0sec.

Rindt was really trying in the Lotus 49C and got down to 3min 30.1sec and Ickx was not far off with 3min 30.9sec. BRM were still having their troubles for Oliver’s engine went sick in the valve department, probably due to over-revving the day before when it kept jumping out of gear, but Rodriguez managed to get in a very competitive time of 3min 31.6sec.

Hill had all the fins and aerofoils put back on the Walker Lotus 49C and the two Matras were proving to be very equal until Pescarolo saw his oil pressure disappear and hurriedly switched off, coasting to a stop at before the engine wrecked itself, though it was the end of his day’s practice. The new De Tomaso had arrived, but like the latest Lotus 72 was being finished off, and in the meanwhile Courage had withdrawn 38/3 as a cylinder head gasket blew.

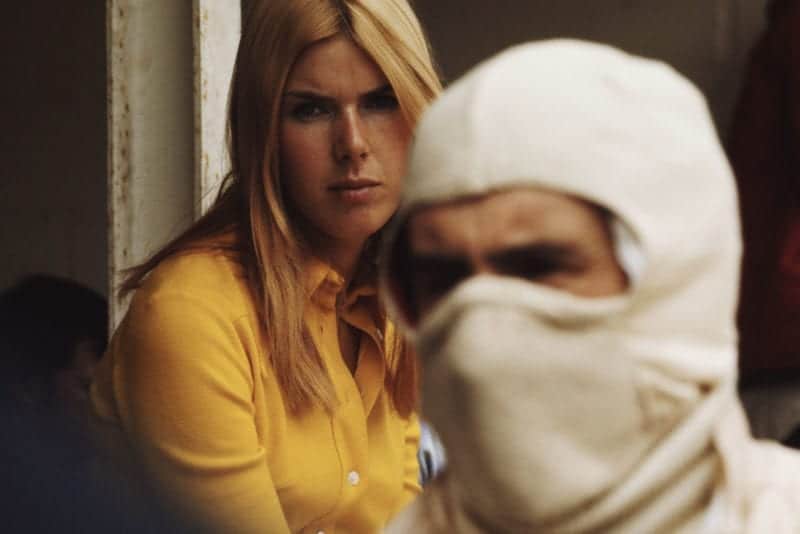

Pole-sitter Stewart is watched over by his wife Helen

Motorsport Images

Oliver’s BRM was rushed back to the garage for an engine change and Rindt’s Cosworth engine went sick, so the car was torn apart behind the pits. The works March cars began to go better and Amon put in a super lap at 3min 30.3sec, third fastest of the early afternoon, but even so it was nearly two seconds slower than Stewart in the Tyrrell March.

It was a good effort by Amon, but when his mechanic looked at the sparking plugs he found the one in number one cylinder was coated with aluminium, so that was the end of that Cosworth engine. It was becoming very obvious that the Cosworth V8 engines were breaking rather disastrously on all sides and there was not the usual happy confidence among those racing with them.

Of the private owners and drivers, Peterson now could use all five gears and was down to a respectable 3min 36.8sec, enjoying the circuit more every time he went out, while Derek Bell in Wheatcroft’s Brabham was thoroughly enjoying himself, having the knowledge of Spa from the 1,000-kilometre race with the Belgian-owned 512S Ferrari, and his best time was 3min 36.2sec.

At 2:30pm practice stopped and there was a welcome break until 6pm, during which time a semi-national event for BMW saloons did their practice. In the paddock all was activity, the Lotus mechanics did a very rapid engine change on Rindt’s 49C, the new Lotus 72 was finished off, Amon’s March was torn apart, the number three De Tomsaso was put to one side and the brand-new one arrived.

The timetable was for one final hour of practice from 6pm to 7pm and this was obviously going to be the “make-it-or-break-it” session as regards the starting grid, for there was no question of qualifying, all 18 entries were acceptable, providing they were fast enough. Although “make it” was the objective “break it” was still popular and Rodriguez stopped abruptly with a connecting-rod broken in his BRM engine.

Amon’s car was in small pieces so he had no hope of practising but Rindt’s Lotus was finished and he bedded things in. The new Lotus 72C was finished and Soler-Roig proceeded to feel his way round the circuit, and Courage got in some laps with the brand-new De Tomaso. Before the hour was up Oliver’s BRM was finished, with a new engine, and he managed to get his fastest lap in, and Siffert finally got into competition, though not for want of knowledge of the circuit or driving ability, he just lacked a raceworthy car.

Stommelen put in his best lap, but Peterson was right behind him, and Giunti beat them both, but so he should with the practice he had had with the 5-litre sports car. Ickx practised with the spare Ferrari until it went wrong, and then went out in 003 and made his best time of all, in 3min 30.7sec, which was the fastest time in this final session.

Stewart being content with a “bedding-in” time of 3min 33.1sec, knowing he had pole position with 3min 28.0sec, over two seconds faster than his nearest rival, and as this was an average speed of just over 150mph, including two 1st gear corners, no-one could say the Grand Prix cars were hanging about. At the entrance to the ess-bend on the Masta straight, which the braver ones took flat-out, without lifting their throttle foot at all, the Matra team had set up an “instant-speed” timing beam, and the fastest recorded time had been Hill in the Walker Lotus 49C, without fins and aerofoil, at 294kph (approximately 182mph).

When all the times of the three practice periods had been shuffled together the front row of the grid comprised Stewart, Rindt and Amon, and as Rindt was driving a Lotus 49C, very similar to the car that held pole-position in 1967, one wondered where the progress had gone in the intervening years. In the final hour of practice Soler-Roig had failed to get in more than two timed laps and in consequence he was ruled out as a minimum of five laps was required.

While the various mechanics slaved away, many of them into the small hours, to prepare the cars for the race, the timid drivers prayed tor Sunday sunshine and the rugged ones just slept, prepared to accept Sunday in whatever form it arrived. The Meteorological people had guaranteed fine weather for Sunday so the start was scheduled for 1pm, with a presentation of drivers at noon.

Race

Chris Amon, Jochen Rindt and Jackie Stewart line up on the starting gird

Motorsport Images

As promised by the Met Man, Sunday was another glorious day, and one of the leaders of the anti-Spa faction amongst the drivers could be heard complaining that it was too hot. One wondered if the GPDA were going to ask to have the start postponed until it got cooler! This particular driver’s team-manager was voicing the opinion that “Spa was too fast and would be finished in two years”.

The more realistic competitors were preparing for a serious motor race, fuel consumption being uppermost in their minds, the Tyrrell team were really well prepared, both 701/2 and 701/7 March cars were ready to race, and no driver could ask for a better team preparation. 701/2 was destined for the grid, but such is the Tyrrell thoroughness that the second car could have been substituted immediately if required.

“In a fantastic burst of sound they roared away down the hill to start the 28-lap race, with Rindt forging into the lead”

Ickx had settled on 003 Ferrari and Courage was going to use 38/2, the latest De Tomaso. The BRM mechanics had worked hard and long and Rodriguez had a new engine in his car, and Pescarolo and Amon also had new engines. Soler-Roig was refused permission to start with the latest Lotu 72 as he had done insufficient practice, and there was a flap in the March camp for Peterson was being held by the police after a traffic fracas on the way to the circuit. Some top-level diplomacy on the part of the race officials got him freed only a few minutes before drivers began to set off on a warm-up lap. As the cars formed up on the “dummy-grid” there was a lot of work still being done and everyone was topping up with petrol, while the Brabhams were being topped up with oil as well.

It was just after 1pm when the 17 cars rolled forward on to the starting grid, and in a fantastic burst of sound they roared away down the hill to start the 28-lap race, with Rindt forging into the lead from his central position on the front row. As they sorted themselves out on the opening lap it was Amon who took command, followed by Stewart, Rindt, Rodriguez, Ickx, Brabham and Beltoise.

At the end of the field Bell headed for the pits to retire, with his gearbox stuck in gear, the change mechanism under the lever in the cockpit having broken. The two-second superiority that Stewart had shown in practice was not making itself evident, and though he took the lead on the second lap Amon, Rindt, Rodriguez and the others were right behind him.

On the next lap Amon retook the lead and Stewart realised that his Cosworth engine was not pulling like it should. Rodriguez moved up to third place, disposing of Rindt with little trouble, and drivers with Cosworth engines were realising that the BRM V12 engine was really getting into its stride in the Mexican driver’s car.

On lap 4 Rodriguez was second and on lap 5 he took the lead, with Amon, Stewart, Ickx, Rindt and Beltoise following. This was the sight that every BRM follower had been waiting to see, and to see it happen on the super-fast Francorchamps circuit was wonderful, there were no arguments, and Rodriguez set a new lap record at 3min 30.8sec – 240.787kph (149.5mph), almost equal to the old Formula One record before the introduction of the Malmedy corner, so this showed the progress made since 1968.

Courage retired the De Tomaso at the pits as the Cosworth engine was rapidly losing its oil pressure and he wisely stopped before it went bang. The race pattern had now settled down, with the BRM setting the pace, the March cars of Amon and Stewart grimly hanging on, Ickx in fourth place, followed by Brabham, Rindt, Beltoise, Oliver, Peterson and Pescarolo. After a gap came Stommelen, Siffert with a very unhappy car, Giunti with the second Ferrari, and Hill and Miles bringing up the rear. At the end of lap 7 Oliver was missing and after they had all gone by he came coasting into the pits with yet another broken engine, but at least he had the satisfaction of watching his team-mate still out in front and looking very sure.

As Rodriguez finished his eighth lap he had a bit of a slide coming out of La Source hairpin and Amon was immediately alongside him as they raced down the hill side-by-side. The March was credited with leading on that lap and they rocketed down to the Eau Rouge bridge, but few people can “sit-it-out” with the tough little Mexican and the BRM took the lead again up the hill.

“As Rodriguez finished his eighth lap he had a bit of a slide coming out of La Source hairpin and Amon was immediately alongside him as they raced down the hill side-by-side”

Brabham had taken fourth place from Ickx and he now took third place from Stewart, and the BRM pit quickly informed Rodriguez that the crafty Australian was on the rampage, but during lap 9 Brabham overshot the Malmedy corner, and had to let Stewart and Rindt go by, Ickx having fallen back behind the works Lotus.

At 10 laps the BRM looked safe and secure in the lead, but Stewart was losing ground, though Amon was keeping up, in second place. As Rindt went past the pits his Cosworth engine made a funny noise and that was the last that was seen of him until he re-appeared at the pits on foot when the leader was on his 24th lap.

Pescarolo had moved ahead of Peterson and joined Beltoise and the two V12 Matras were singing round in close company, making a beautiful sound as all 24 cylinders pushed out their power at 10,300rpm. Brabham was making up time again after his overshooting of the Malmedy turn and once more the BRM pit warned Rodriguez, for the Australian set a new lap record at 3min 29.5sec, and disposed so smartly of Stewart that it was very obvious that all was not well with the Tyrrell March.

Rindt leads the field up the hill

Motorsport Images

As Stewart left La Source at the end of lap 14 the car suddenly slowed, the driver quickly raised an arm and then there was a great plume of smoke as the Cosworth engine broke in a big way, and Tyrrell had to watch the wreckage coast by to the foot of the hill. On the previous lap Miles had stopped at the pits with the Lotus 72, having spun at the sharp left-hand bend at Les Combes, and it was found that both rear tyres had lost nearly all their pressure. As the fuel system overflow had been exhausting fuel into the engine intakes on acceleration (that has happened before!), and the gearbox was playing up, all of which had put the car into a very poor last place, it was withdrawn.

“The BRM was really singing round in the lead, Rodriguez not straining it at all”

The BRM was really singing round in the lead, Rodriguez not straining it at all and only using 10,200rpm, whereas he had 10,700rpm available. Even so he was lapping faster and faster as the fuel load lessened and he set up a new lap record with 3min 28.9sec and then 3min 27.9sec, and all the while Amon was pressing the March as hard as he knew how, staying two seconds behind the BRM all the time and virtually lapping at the same speed.

Behind these two Brabham was in third place, but unable to challenge the increased speed of the leaders, and Ickx was in an uninspiring fourth place, the Ferrari flat-12 sounding healthy enough. Then came the two Matras, occasionally swapping places with each other, and one wondered if a top driver might not have been able to put the French V12 up at the front with the British V12.

Giunti was driving a nice regular race but was black-flagged as someone reported the Ferrari was losing oil. He stopped at the end of lap 18 but no oil leaks could be found and he went off back into the race, having lost a place to Stommelen.

On the previous lap Hill had stopped at the pits with a rear tyre losing bits of tread, having felt the roughness going through the Burnenville curve, and stopping at Malmedy to investigate. He was having a very dreary race as the Lotus had stuck in top gear for a time and he was now a lap behind the leaders.

Peterson’s March split an exhaust manifold pipe and Crabbe called him in to have it changed, a very hot and difficult job for the mechanics, which dropped the Swede from a very steady eighth place to dead last, too far back to qualify as an official finisher. Brabham was suddenly reported as going slowly at Stavelot and he eventually coasted into the pits and out of the race, the clutch ring having disintegrated and put the whole thing out of balance.

At 20 laps there was still two seconds between the leading BRM and Amon’s March, and Rodriguez was clearly in full command. Ickx went by slowing visibly, in trouble with petrol seeping into the cockpit from a leak at one of the fuel pumps, and two laps later he was too uncomfortable to continue so stopped at the pits. While the leak was cured he put on some dry overalls and set off again, but now in last place, apart from Peterson who was still at the pits.

Hill’s Cosworth engine broke out on the circuit, and the Lotus stopped at Blanchimont rather suddenly, and Stommelen was having a recurrence of gear-change trouble that had held him up earlier, this finally manifolding itself in trouble with the gear-lever mechanism. Giunti was still running strongly and caught and passed Stommelen, taking fifth place, but the Matra of Pescarolo, which was in fourth place, had lost its sharp edge and was losing contact with its team-mate. After Ickx had stopped at the pits Beltoise had taken over third place, a long way behind the leaders, but even so the two French cars had been making an excellent impression.

Rodriguez stands on the podium for the second time in his career

Motorsport Images

On Pescarolo’s car the alternator had stopped charging and the battery was running down, affecting the fuel pumps and injection pressure pump, but giving all the symptoms of being low on fuel in the tanks. With one lap to go he was forced to call at the pits and more fuel was put in, but this was not the answer, and the battery would not turn the starter. Meanwhile Amon was still hammering away at the BRM, but to no avail, Rodriguez was sitting a comfortable two seconds ahead, the two of them circulating faster and faster.

To the delight of all the BRM fans, and especially to the Rodriguez fans, the quiet little Mexican accelerated down from La Source hairpin for the last time, with Amon just over one second behind, having done his last lap in a new record time of 3min 27.4sec. After a long period of domination the Cosworth engine had finally been well and truly beaten by a 12-cylinder engine and everyone was pleased for BRM, for they had tried so hard for so long to break the V8 monopoly, and had now done it on the fastest of Grand Prix circuits, in a magnificent manner.

“Everyone was pleased for BRM, for they had tried so hard for so long to break the V8 monopoly”

Amon had driven one of his hardest races, but freely admitted he could do nothing about the speed of the BRM, only hoping that if he kept up the pressure the 12-cylinder from Bourne might break, but it did not. Beltoise finished in third place, the Matra sounding as crisp as ever, Giunti completed his 28th lap, moving up into fourth place as he did so, and Stommelen limped round on his last lap to take fifth place, these two taking places from the unfortunate Pescarolo who was stuck at the pits, having completed only 27 laps.

Siffert, who had had a miserable race with a car that just would not go properly, failed to finish, coming to rest out on the circuit with loss of fuel pressure as the leader got the chequered flag. It had been a superb race, with BRM winning convincingly, not by reason of the default of others. From his third-row starting position Rodriguez had forged through to the front, aided by the power and speed of his BRM, and his obvious enjoyment of racing round the fabulous Francorchamps circuit at an average speed of 150mph, reaching nearly 187mph down the Masta straight. It was motor-racing beyond the imagination of ordinary mortals.