1966 Le Mans 24 Hours race report: Ford takes first win

The Ford GT40s finish one-two, Bruce McLaren and Chris Amon taking the American marque's debut victory over the Ferraris

Motorsport Images

Le Mans, France, June 18th/19th.

This year Ford came to Le Mans in a much more organised manner than in the previous two years and the whole Detroit-supported project looked much more likely to achieve success than previously. There were eight 7-litre Mk. II Ford racing coupes, three run by Shelby American, three by Holman and Moody and two by Alan Mann Racing and all the cars were prepared to the same specification, differing only in colour, which was done for identification purposes, but unlike in previous years this was a concerted and united effort controlled much more strictly by Ford staff.

In direct opposition were two works 330P/3 Ferrari coupes and an open 330P/3, the last on loan to Chinetti’s N.A.R.T. team. Backing up the works Fords were numerous private teams running 4.7-litre GT40 models, and on the side of the works Ferraris were private teams with 365P/2, 275LM, Dino 206 and GTB models, but the atmosphere at Le Mans was much stronger than Ford versus Ferrari, it was America versus Europe, and the United States had added strength in their armoury from a lone Chaparral, while Europe had Porsche to rely on for solid support.

During practice America showed its strength when Gurney made fastest lap at a staggering 3 min. 30.6 sec., an average speed of 230.102 k.p.h. (approx. 142.8 m.p.h.) and he was not alone, for the other Fords were right behind him and the Ferraris could only manage to get in the midst, being overwhelmed by sheer numbers. Before practice finished both sides had been struck a severe body blow, for Surtees had an altercation with his team manager and went off in a huff, just when Ferrari and Europe needed him most, and one of the Ford drivers, the American Dick Thompson, caused an accident and did not comply with the rules about reporting it and was disqualified. As he was co-driver to Graham Hill in one of the Alan Mann cars this was a serious blow indeed, but some rushing around got Brian Muir, the Australian saloon-car driver, over as a replacement. Ford had already had to solve a lot of driver problems for accidents had prevented Foyt, Ruby and Stewart from joining the team as arranged.

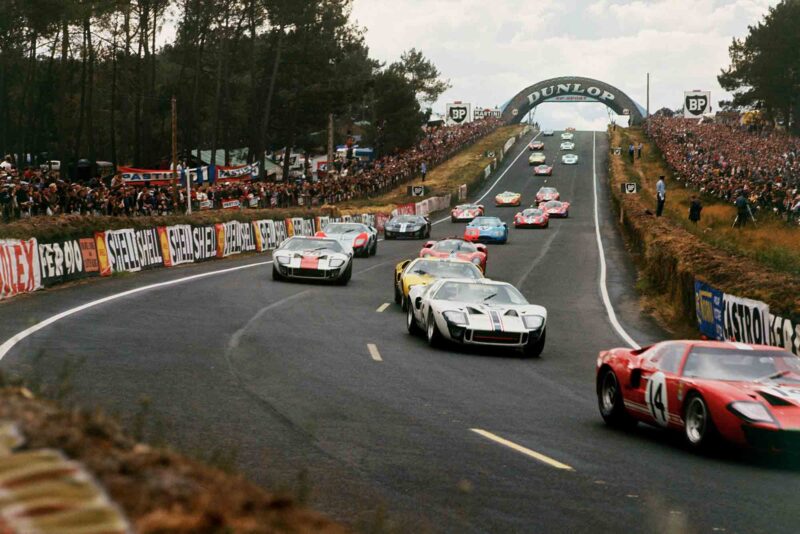

The days prior to the race had been extremely hot, but Saturday was rather ominous, with gathering clouds and a much lower temperature and thirty minutes before the traditional 4 p.m. start a drizzling rain began, causing a lot of tyre changing, both as regards tread pattern and make, however, the rain did not develop quite as anticipated so that some people were caught out. Henry Ford II was invited to drop the starting flag and send the 55 drivers running across the track to their waiting cars to start the Grand Prix d’Endurance, or 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Drivers run to their cars at the start of Le Mans ’66

Motorsport Images

The line-up was in order of practice times and from Gurney at the head with the red 7-litre Ford there was a long line of very powerful and very fast cars, probably more than Le Mans has seen before, which made one rather apprehensive of some of the tiny cars and inexperienced drivers at the lower end of the row. In the solid phalanx of Ford machinery the Ferraris were fifth, seventh, eighth, fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth, with the Chaparral tenth, which was not a very hopeful situation for Europe, considering the cars had not yet started their first lap.

Graham Hill led the opening stage, followed by Gurney, these two running away from the rest of the field, but European hopes rose as three Fords headed for the pits at the end of the opening lap. Ken Miles stopped very briefly to have his door shut, Whitmore came in to stay for repairs with a broken brake pipe and Hawkins limped in with a broken drive-shaft, which had given him some exciting moments at the end of the Mulsanne straight. Rodriguez in the N.A.R.T. Ferrari P3 had made a terrible start but recovered quickly and by 4.30 p.m. he was in fourth place, ahead of Parkes, but Gurney, who now led Hill, and Bucknum were all out of sight. Miles was travelling very fast and making up time for his stop, and although Ford tactics had called for 3 min. 36 sec. laps some of the 7-litre cars were nearer 3 mm. 33 sec. a lap and there was a bit of a free-for-all going on.

In the 2-litre category, which was all-European, but nevertheless very interesting, Porsche were leading from Matra–B.R.M., while two of the Dinos had fallen by the wayside and by 5 p.m. the remaining Dino was in trouble and on its way out, so that Ferrari’s small arms had proved quite useless as supporting forces. By this time Gurney was way ahead, with Graham Hill holding second place, Bucknum third. Rodriguez fourth and Miles up in fifth place after lowering the lap record successively to 3 min. 33.1 sec. Bonnier in the Chaparral was next, then Parkes, Guichet, McLaren and Bianchi, so the situation was Ford, Ford, Ford, Ferrari, Ford, Chaparral, Ferrari, Ferrari, Ford and Ford, with more following. During the second hour rain began to fall as refuelling stops became due and this caused a minor panic as well as numerous heart-searching decisions about further tyre changing. The yellow Ford of Whitmore/Gardner and the bronze one of Hawkins/Donahue had both been repaired and gone out again, but neither were very fit and were back in the pits when the leaders came in for fuel, which caused something of a shambles due to lack of space and Graham Hill just could not find room and had to go on for another lap.

The field scrambles away at the start

Motorsport Images

After this commotion the order was cars number 3, 1, 27, 5, 7, 20, 21, 2, 6, 18, with Ginther doing his best in the P3 Ferrari, but Ford overwhelming by numbers, Denis Hulme took over from Miles and continued the good work taking the lead from Gurney’s partner Jerry Grant, while Muir was doing a remarkable job bearing in mind he had not sat in a Ford GT or seen Le Mans until the morning of the race. Even before darkness fell the pace was beginning to take its toll and many of the weak as well as the strong had fallen out, Ford number 4 having a broken differential and number 8 being delayed further by a defective clutch-operating mechanism, which put it behind the minimum regulation distance, so it was withdrawn.

“Muir was doing a remarkable job bearing in mind he had not sat in a Ford GT or seen Le Mans until the morning of the race”

Two of the small cars, a 6-cylinder ASA and a Peugeot 204-engined C.D., caused a worrying diversion by getting tangled up on the Mulsanne straight and catching tire, luckily without serious hurt, and before midnight it looked as though the American might was beginning to stumble. Graham Hill walked back to the pits having left number 7 by the roadside with broken suspension, and number 6, the Bianchi/Andretti car, had broken its engine; the Chaparral had gone out ignominiously with a flat battery, but number 20 Ferrari had gone out with a flourish when Scarfiotti collected a C.D. in the Esses and Schlesser had been involved through there suddenly being nowhere for him to aim his Matra without having an accident, which was very hard on the French firm.

At midnight Gurney/Grant (Ford), Miles/Hulme (Ford) and Rodriguez/Ginther (Ferrari) had all completed 126 laps, while McLaren/Amon (Ford) were one lap behind, Mairesse/Muller (Ferrari) were four laps behind and Bandini/Guichet (Ferrari) were five laps behind. Ford’s supporting forces were moving up, but immediately behind them were four Porsches presenting a very solid front, running splendidly and with no troubles at all. One hour later the Mairesse/Muller Ferrari had dropped back a place and there were only thirty-two cars left running and the cold and damp night was beginning to reach its lowest ebb. It is at this time of the race that unexpected things seem to happen, and true to form trouble struck both camps, with the Rodriguez/Ginther Ferrari going out with gearbox trouble and one of the private Fords of the Essex Racing Team going out with a broken engine.

Ford GT40s lead the way at 1966 Le Mans start

Motorsport Images

At 3.30 a.m. Muller brought the Swiss Ferrari into the pit with its gearbox broken and the remaining works Ferrari was delayed by a broken brake pipe. As dawn broke the list of runners had diminished to twenty seven and Fords filled the first six places, followed by the works Porsches, while such Ferraris as were running were either sick or tired. The three GTB Ferraris were still running perfectly, but of course could not hope to match any of the prototypes for speed. As the world of the 24 Hours began to wake up and the sleepy ones came to life again Ford lost a steady runner when the Ligier/Grossman GT40 went out with engine trouble and Ferrari looked like losing the N.A.R.T. GTB Ferrari as its clutch and gearbox were breaking up.

Just after breakfast (8 a.m.), there was strife in all directions, for the sole remaining P3 Ferrari had been suffering from an internal water leak in the engine and a slipping clutch, and it finally succumbed, while Spoerry crashed the Filipinetti Ford GT40 he had been sharing with Peter Sutcliffe and the Belgian 275LM Ferrari staggered to a final halt at the pits having been losing water and overheating for a long while, but even more serious was the fact that the Gurney/Grant Ford was beginning to show signs of failing. There were now only twenty-four cars in the race, and it was barely mid-morning when gloom descended on the Shelby pits as car number 3 came slowly in to retire, having lost its water, overheated, and was unable to replenish anyway due to the rule demanding a certain distance between taking on fluids other than petrol.

The N.A.R.T. GTB Ferrari was disqualified for transgressing the rules when starting away from the pits without a clutch, and although Fords were in the first three places with the only three Mk. II cars running they were not terribly confident, seeing victory approaching but knowing how things can still fall apart in the last few hours of Le Mans. In order to cut out any possibility of a nonsense that might make team personnel make a mistake the Ford pits got tough and cleared out all the “hangers on” and the myriad of photographers and TV and radio people, who invariably get in the way, and quite rightly so, for they had a lot at stake and had worked fantastically hard to reach this point at Le Mans, a point that was by no means a certain victory for them. The fact that the race was not yet won was brought home with a jolt when two of the small cars which had been running like clocks suddenly blew up; the second Austin Healey broke its head gasket and an Alpine broke its water pump, the first Healey having expired with clutch trouble.

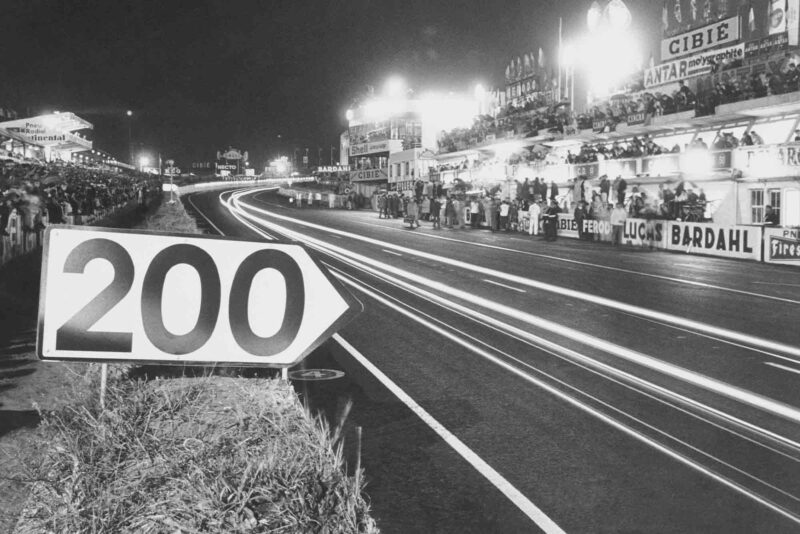

The action continues into the night at Le Mans ’66

Motorsport Images

At noon, with four hours still to run, there were only sixteen cars left running, the three Fords, with the McLaren/Amon car now slightly in front of the Miles/Hulme car, the Bucknum/Hutcherson Ford was nine laps behind, and then came a whole row of Porsches making a stupendous impression by the way they were still cracking round and sounding indecently healthy, while the remaining Alpine-Renault Gordinis sounded as if they had only just started the race, and most incredible was the fact that the lone French-driven Mini-Marcos was still buzzing round. By 2 p.m. rain started and everyone began to go very gently, not wishing to make any silly mistakes at this late hour.

With barely 1 1/4 hours left to run there was horror in the Porsche pits as the Gregg/Axelson car arrived with a dead engine and something broken in the valve gear. This caused some alarm and despondency for the last thing that anyone expected was for one of the very healthy Porsche engines to break at this late stage. The Maranello Concessionaires Ferrari GTB driven by the two well-known Formula Three drivers, Pike and Courage, had been going like a train, and suddenly a brake pipe was broken and Pike had to stand in the pits and restrain himself while it was mended and the system was bled of air, all of which was very frustrating at this late hour, but it did make people realise that no race is ever won until the end and Le Mans does not finish until 4 p.m. on Sunday.

“The over-acting of the Shelby team had back-fired on them: McLaren and Amon were received as rather surprised and dissatisfied winners”

In the final hour the rain ceased but the roads were streaming wet and the big Fords really looked like power boats as they circulated. Shelby still had his two cars running; Holman & Moody their sole survivor; Porsches had five very healthy cars and a sick one that was hoping to set off and complete one final lap as 4 p.m. arrived. Alpine had four of their remarkably fast little 4-cylinder prototypes still running, the Mini-Marcos was still there, and the only Ferrari survivors were two standard production GTB coups.

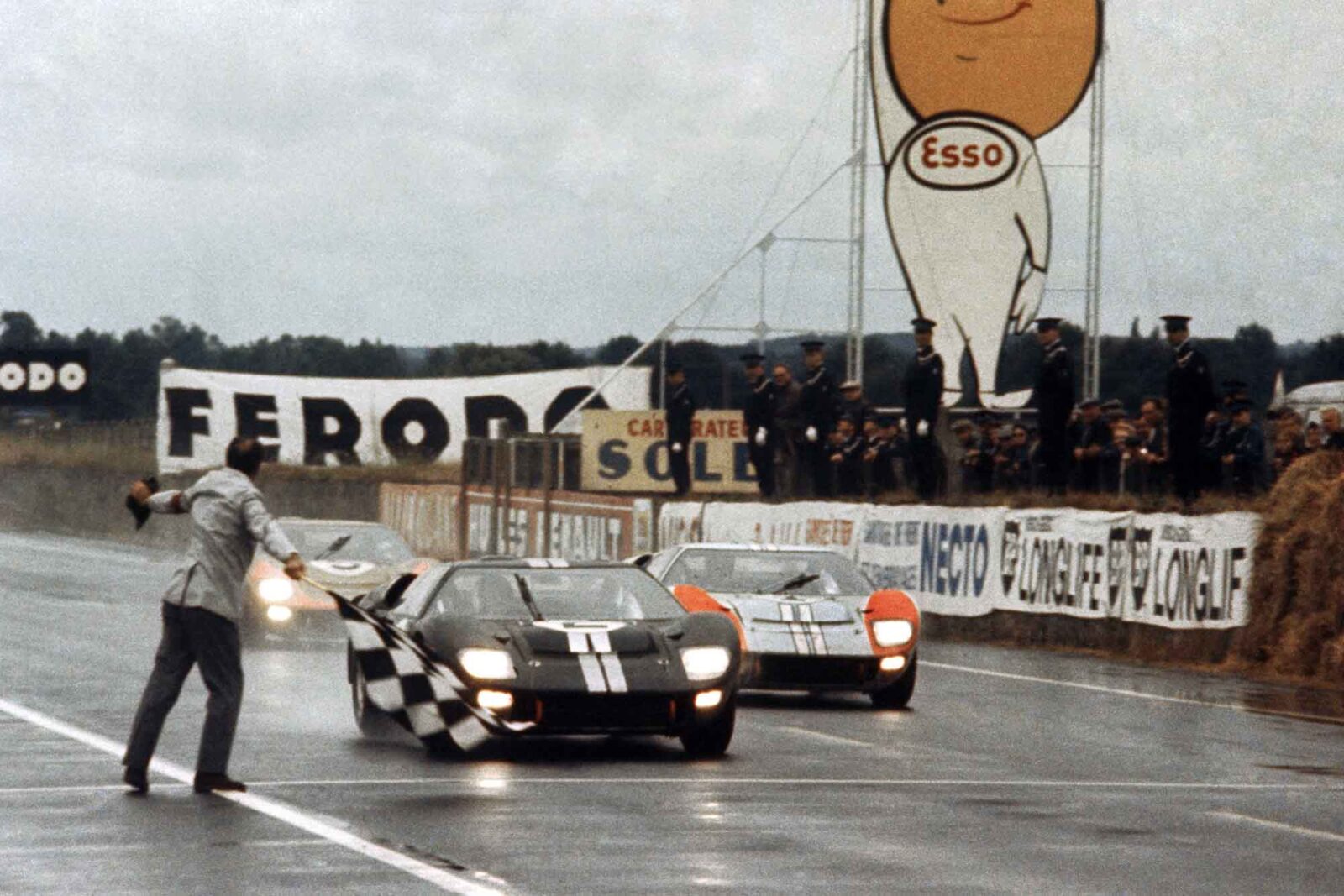

During the last half-hour the two Shelby cars closed up together, Miles waiting for McLaren, who had lost the lead during the final pit stops for refuelling, and the light-blue and the black 7-litre Fords circulated quietly together, gathering up the gold car of Bucknum as they started what was obviously going to be their final lap and a thoroughly well deserved victory for Ford, won through pulverising the opposition, even at the cost of heavy losses to their own forces. The atmosphere was still very wet and damp as the survivors toured round on their final lap, endeavouring to arrive at the finish as near to 4 p.m. as possible. By a prearranged plan the Fords of McLaren and Miles arrived, headlights ablaze, in as near a dead-heat as they could judge, with Bucknurn just behind them. It was indeed impressive and an undisputed victory, but the powerful line of Porsches was something of which Stuttgart could be very proud, the only blemish being that the sick car could not drag itself away on its last lap and had to be abandoned leaving fifteen survivors in the hard and bitterly fought race.

Chris Amon greets the crowd after taking his and Ford’s debut Le Mans victory at Le Mans

Motorsport Images

The celebrating was dampened somewhat when the timekeepers announced that McLaren and Amon had won, a dead-heat being impossible as the cars had started at 4 p.m. on Saturday with the Miles/Hulme car already some yards ahead on the starting grid, so that as they had arrived side-by-side on the same lap on Sunday at 4 p.m. the McLaren/Amon car must have covered a greater distance in the 24 hours, the difference being quoted as twenty metres. The over-acting of the Shelby team had back-fired on them and McLaren and Amon were received as rather surprised and dissatisfied winners. Colin Davis and Jo Siffert won the Index of Performance with a works Carrera Six Porsche running on fuel injection, and they also won the 2-litre class, having dominated it throughout the 24 hours.—D.S.J.

Le Mans Lights

As and when the brake discs on the Fords became worn they were changed in their entirety, the disc being retained in place by the road wheel and easily detachable, using asbestos gloves. Three Matra-B.R.M. 2-litre V8s took part but all fell out for troubles of a tiresome nature, the worst being a seized ZF gearbox on the Servoz-Gavin/ Beltoise car; Schlesser crashed and the Jaussaud/Pescarolo car went out with trouble in the injection pump drive department. The only claim to fame for the Bizzarrinis was that the rear-engined open one actually managed to spin away from the Le Mans start!

The prize for endurance must surely go to the variety artist behind the grandstands who played an accordion for 24 hours non-stop, accompanied by a long line of guitar players who took shifts to keep up with him. It was a fine and powerful American victory, even if the first two cars were driven by two New Zealanders and a New Zealander and an Englishman. The third place car was driven by American Honda driver Ron Bucknum and NASCAR Stock-Car driver Dick Hutcherson, driving in his first sports-car race. Not only were the first three cars American but all were using American Goodyear tyres. However, all the remaining finishers were on Dunlop tyres. A lot of people said the Ford victory showed you could win Le Mans if you poured in sufficient dollars, but anyone who believed this had no idea of the fantastic amount of work put into the project from the time of the arrival in France, let alone in America.