1964 Dutch Grand Prix race report: Another Clark masterclass

Jim Clark laps all but one of the field in a dominant Dutch performance; Scot now level with BRM's Graham Hill on championship points

The field scrambles away at Zandvoort

Motorsport Images

The organisation of the Dutch Grand Prix this year was undertaken by the NAV, a sporting association acting on behalf of the KNAC, rather like the BRDC running the British Grand Prix for the RAC, and this new organisation invited a carefully selected field of eighteen drivers to take part. It went without saying that all the works teams were included, and the only regulars who were missing were the British Racing Partnership drivers.

The Ferrari team of Surtees and Bandini were both entered on V8 Ferraris, with a V6 Ferrari as a spare, the BRM pair, Graham Hill and Ginther, had two 1964 cars that they had used at Monte Carlo, as did Brabham and Gurney with the Brabham cars, and Clark and Arundell with the Lotus cars, while McLaren and Phil Hill had 1964 Coopers and Amon and Hailwood had the Parnell Lotus 25 cars. Bonnier had Rob Walker’s new Brabham-BRM and Siffert had a similar car, while Anderson had his new Brabham-Climax. The Centro-Sud BRM cars were driven by Maggs and Baghetti, and de Beaufort completed the list with one of his old 4-cylinder Porsches.

Qualifying

The Zandvoort circuit being a private track in its own grounds, it was easy to provide ample time for practice, and it began on Friday morning at 10am, going on for two hours. Surtees was out in the V8 Ferrari he had driven at Monte Carlo, the defective ball-races in the gearbox having been sorted out, and Bandini was out in the V6 Ferrari, the second and latest V8 car not being ready to run; as far as the eye could see this new car was identical to the one Surtees was driving.

Brabham and Gurney were out in the two Brabham-Climax cars, the Australian having to get on with the job of making a good time at once, as he was planning to fly to Indianapolis after this first session. In actual fact both Brabhams were going well and Gurney was setting a good pace. The two Lotus-Climax V8 cars were the 25C and 25D that were used at Monte Carlo, the 25C of Arundell now having the Type 33 drive shafts as on Clark’s car, though he was still using the Type 25 rear suspension, but had a complete Type 33 steering assembly, whereas Clark’s car was still using a Type 25 rack-and-pinion assembly. Both cars were using new strengthened mounting brackets for the rear anti-roll bars, for contrary to many reports the breakage at Monte Carlo had nothing to do with Clark hitting the straw bales, the designer of the brackets admitting that he had cut things a bit fine in his search for weight saving.

The works Cooper cars were the 1964 ones, now with radius rods from the outer extremity of the upper front rocker-arms of the suspension, back to the chassis frame by the cockpit. This modification was to try and cut out some of the “flapping” that took place under heavy braking, which may have been a contributory cause of the broken steering arm that McLaren had suffered at Monte Carlo.

The 1963 car he drove there was in the Cooper garage in Zandvoort, completely dismantled but forming a source of spare car. After their sweeping success at Monte Carlo the BRM team had only to prepare the cars in the same manner and ensure reliability and efficiency, there being no need to do any redesigning or rebuilding. The Centro-Sud team had gathered together some mechanics and got their two 1963 BRM V8 cars prepared, but without the guiding touch of works mechanics the cars were down on performance.

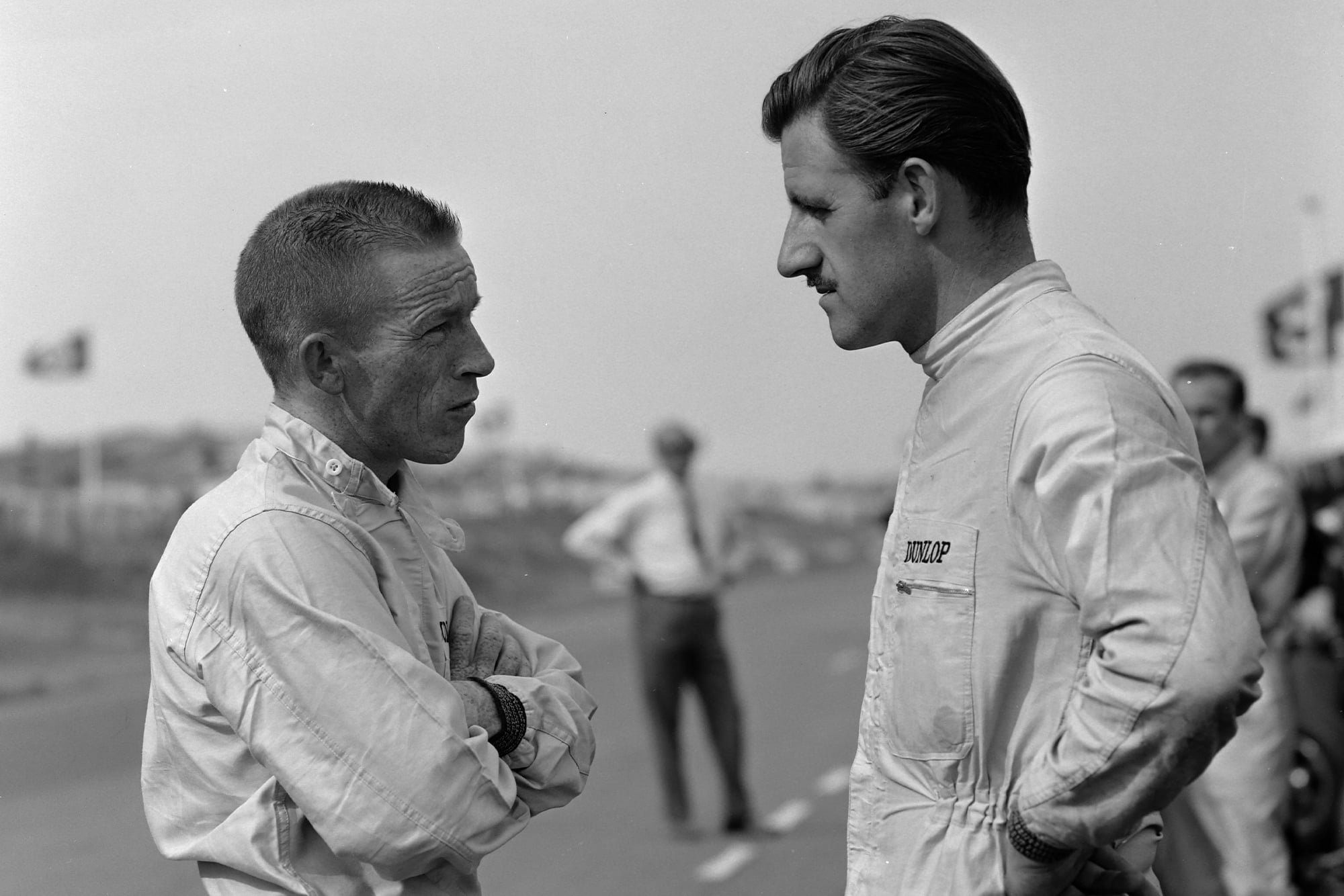

BRM team-mates Ginther and Hill confer

Motorsport Images

The Parnell team had modified Amon’s Lotus-BRM V8 to take the new 13in Lotus wheels and wide-tread Dunlop tyres, this involving the use of Lotus 24 front suspension uprights in order to get the hub centre height correct, and altering the angles of the rear suspension members accordingly, and by the way Amon was going they had obviously done a good job. Hailwood’s car was as he had raced it at Monte Carlo, the skilful repairing of the Lotus “monocoque” still being race-worthy.

Of the private owners, Anderson was going well, in spite of having an old-type Climax V8 using Weber carburetters, whereas all the other Coventry-built engines were on Lucas fuel-injection. Bonnier had Walker’s new Brabham-BRM V8 with 6-speed Type 34 Colotti gearbox, but was also using Walker’s 1963 Cooper-Climax, but did not take long to decide which car was the better, the Brabham being much faster. The only people not out for the first practice were de Beaufort, who was late in arriving, and Siffert, whose mechanics were still putting the finishing touches to his brand new Brabham-BRM V8 with 6-speed Colotti gearbox, having been at the Brabham works for the past week building the car.

Although the lap record stood at 1min 33.7sec to Clark with a Lotus-Climax in last year’s race, he had done 1min 31.6sec in practice, and with the new Dunlop “wonder tyres” and a Climax engine giving a good 200bhp it seemed that 1min 30sec might be approached. In spite of perfect weather conditions the fastest lap in the morning session was 1min 31.2sec by Gurney with his Brabham-Climax, closely followed by Clark with 1min 31.6sec. Most of the team time-keepers in the pits adjudged that these times should have been reversed, but you cannot argue with the official time-keepers, so Gurney was credited with the fastest time. Comment on this question will be found elsewhere in this issue.

There was nobody else in the class of these two in this first practice period, but after lunch there was another two-hour session, and Graham Hill joined them with a time of 1min 31.4sec, but Clark improved to 1min 31.3sec, though Gurney was slower. Brabham was well on his way to America, and de Beaufort arrived with his old Porsche.

The Ferrari team were still using only one V8-cylinder car, the new one not being ready, and Surtees was in trouble with an oil leak from an inaccessible union on the front of the engine. Bandini was still training with the V6-cylinder car and going quite well, but the works Coopers were not handling to the satisfaction of the drivers and nothing that was done seemed to improve matters.

“Clark took time off to show Arundell the way round the circuit, the two cars running nose-to-tail for a while, until Clark speeded up and Arundell lost his ‘guiding light’”

Team Lotus were so confident that Clark took time off to show Arundell the way round the circuit, the two cars running nose-to-tail for a while, until Clark speeded up and Arundell lost his “guiding light,” being unable to stay with Clark on braking, and cornering on the very fast 5th-gear curves on the back of the circuit. Hailwood’s practice finished abruptly when a crown-wheel and pinion broke in the Hewland gearbox of his Lotus 25. The positions on the front of the starting grid now stood to Gurney, Clark and Graham Hill, all three being in the 1min 31sec bracket.

The final practice session was on Saturday afternoon, for a further two hours, and though none of the front-row contenders improved on their times, most of the other runners did. Conditions were still good, the keen and biting winds so often prevalent at Zandvoort this year being nice and warm. Bandini was now out in the new Ferrari V8, but Surtees was still having troubles, this time with a leaking radiator, which was changed behind the pits. Cooper’s seemed to be improving their cars worse, and though Phil Hill finally got his in some sort of shape so that he felt confident to go faster, the time-keepers insisted that he was actually slower than before!

Dan Gurney puts his Brabham on pole

Motorsport Images

Both the Lotus and the BRM teams were well under control, having time to sit around and wait until conditions suited them, for there was no point in wearing the cars out by practising all the time. Hailwood could not practise as his gearbox was still being repaired, but Siffert at last got his new Brabham completed and began the bigger job of getting it to work properly. Clark once more went out with Arundell following him closely, but as soon as he started to try his team-mate fell back, and though Arundell had various settings, such as camber angle and toe-in, altered, he could not match Clark’s times; even so he was doing some very creditable times, his best being 1min 34.0sec, which was as fast as Ginther.

Towards the end of practice the Ferrari team seemed to be getting is a muddle, for Surtees tried the new Ferrari V8 and Bandini went back to the V6 car, and then the old V8 was repaired and Surtees went back to that, and by the time practice finished there had been a lot of number swapping and nobody seemed too sure who was to drive what. Cooper’s were still in a bit of a shambles, but McLaren managed to get in a fairly fast lap, while Brabham’s time that he did on the Friday morning was good enough to keep him in the third row of the start.

Amon achieved the remarkable record of his best time in each practice session being 1min 35.9sec, so that he could rest assured that he had reached his limit. The Centro-Sud BRMs were having this and that altered, and though Baghetti was not very fast, Maggs was beginning to get into a faster stride when he went off the road and overturned; luckily without personal injury but with some damage to the car.

Race

Clark leads the field

Motorsport Images

Sunday was a glorious day and an enormous crowd flocked to the circuit, the lunch period being taken up by some National races, while the Grand Prix was due to start at 3:15pm. Brabham had returned from Indianapolis that morning, having qualified to start in the 500-mile race, and everyone except Maggs was ready to start, the Lotus mechanics being so confident that they spent a lot of the morning polishing their cars.

Surtees had the new V8 Ferrari, but it was fitted with the nose cowling and windscreen off his earlier V8, and as it did not fit too well the unpainted gap along the top of the side tanks was covered up with red masking tape. Bandini arrived with the V6 car, but before the start his numbers were transferred to the older of the V8 cars, and the nose, cowling from the new one was fitted to it.

The reason for this changing of nose cowlings and windscreens was that the screens were moulded and shaped to suit the individual drivers, as regards angle and height. The drivers were all taken for a lap of the circuit sitting in open sports cars, and then the signal was given for the Grand Prix cars to do a warming-up lap, but for some strange reason nobody was in a great hurry to do this and it was nearly 3:25 pm before all the cars were assembled behind the starting grid.

The new “dummy grid” system of starting was employed, the engines all being started on the 3-minute signal, which seemed an absurdly long time to keep them running before moving forward onto the grid proper. However, all went well and seventeen cars rolled gently forwards to their grid positions to await the final 30 seconds before starting the 80-lap race.

All three drivers on the front row overdid the wheelspin and looking at one another and realising this they all kept the throttles well open, so that the cloud of rubber smoke was most impressive, even if the acceleration was not as much as it might have been. Side by side they raced for the first corner, and Gurney on the inside was the first to brake, which let Clark and Hill go into the corner first, with Clark on the inside; Hill did not give up and kept alongside Clark all round the 180-degree turn, but the Scotsman had the shorter distance to go and was in front as they left the corner.

“All three drivers on the front row overdid the wheelspin and looking at one another and realising this they all kept the throttles well open, so that the cloud of rubber smoke was most impressive”

From that point onwards the outcome of the race was settled, for Clark streaked into a lead that was to increase with every lap. Graham Hill, Gurney, Arundell, Surtees, Phil Hill and McLaren chased him for the first lap, but by the end of the second lap only the first four were able to keep Clark in sight, the two works Coopers of Hill and McLaren dropping back, to be challenged by Ginther’s BRM.

On lap three Surtees passed Arundell and on the next lap the number two Lotus driver showed signs of being unable to keep up the pace of the leaders. After five laps Clark had a 3sec lead over Graham Hill, while Gurney and Surtees were right behind the BRM. This was a tidy situation, for most people will agree that this quartet forms the cream of Grand Prix racing and any one of them is capable of leading or winning a Grand Prix race. If any other driver leads this group it usually means that some unknown factor has crept in.

As they were driving, respectively, Lotus-Climax, BRM, Brabham-Climax and Ferrari, it indicates a pretty healthy state of affairs in Grand Prix racing. These four pulled steadily away from the rest of the runners, with Clark gaining fractions of time all round the circuit that were rapidly adding up into seconds, and at an average of over 100mph this represented a considerable distance.

Hill battles with Gurney

Motorsport Images

Of the rest of the competitors, Bandini had been running on what sounded like seven cylinders ever since his warming-up lap, Siffert had gone into the pits on lap two with fuel system bothers in his too-new Brabham, Arundell was driving a fast but lonely race in a very sound fifth place, Brabham was beginning to work his way out of the mid-field, Amon was going well and keeping up with Ginther, while Anderson and Hailwood were having a private battle. Bandini in the sick Ferrari and Baghetti, going comparatively slowly in the red BRM, were bringing up the rear, as de Beaufort had already retired with engine trouble in his usually reliable Porsche.

On the sixth lap Clark had set up a new lap record in 1min 32.8sec, and after that he was continually lapping at around 1min 33.0sec, the Lotus handling much better with full tanks than with near-empty ones. At ten laps his lead was close on 4sec, and by fifteen laps it had increased to nearly 5sec, and as the cars were passing the pits at about 140mph this 5sec seemed much longer. After racing in close company for a number of laps, Surtees got by Gurney on the 10th lap, but Gurney hung on after that and Graham Hill was not really losing them. After struggling round for it laps Bandini went into the pits to see if anything could be done, and it was not until lap 21 that he rejoined the race, with the same erratic-running engine, a change of plugs and some prodding and poking finding nothing apparently wrong, the trouble lying in the injection unit.

By 20 laps Clark’s lead was near enough 10sec, while Hill, Surtees and Gurney were quite close together, then 38sec back came Arundell, followed by Brabham, who was 46sec behind the leader. McLaren was doing his best to keep in the slipstream of the Brabham but was having a hard time as the Cooper was not handling at all well. At 56sec behind Clark came Amon, now leading Ginther, and following them were Phil Hill, Bonnier, Anderson and Hailwood, while Baghetti had already been lapped.

At the end of the 22nd lap Gurney was seen to have lost ground on Hill and Surtees, and on the next lap he came slowly into the pits with a feeling that something was wrong with the back suspension. He sat in the cockpit while his mechanic pushed and pulled everything without finding anything wrong, and then Gurney noticed that one of the spokes of his steering wheel had cracked at the hub. It was obviously this that had given the feeling of instability, and as there were still 56 laps to go and he had lost contact with the leaders he gave up, there being no spare steering wheel available.

While this had been happening Graham Hill’s BRM had begun to misfire and Surtees had got by him into second place. The BRM trouble got worse until the engine was cutting out completely, as if the ignition had been switched off; there would be a pause and then it would come in again with a bang on all eight cylinders. The trouble lay in the fuel system where high temperatures in the cockpit were affecting the Lucas pressure pump for the injection system, vapour-locking taking place either in the pipes or in the pump itself, which is mounted horizontally in the floor of the car with an air scoop underneath.

“Hill had his foot hard down his eyeballs were nearly falling out!”

Each time a bubble of vapour reached the injector unit the engine would cut dead and Hill would be thrown forwards as if he had stamped on the brake pedal. Then the bubble would pass, fuel would arrive, and the engine would cut in again, usually on full throttle as Hill had his foot hard down, and the violent acceleration would jerk his head backwards. Out of some corners this sequence of events would happen three or even four times in quick succession, so that Hill’s eyeballs were nearly falling out! He rapidly lost ground to the leaders and looked in danger of losing his third place as Arundell was not far behind.

The Lotus pit was urging its number two driver to “press on” as Brabham was beginning to look threatening in fifth place, and Arundell responded splendidly, having two objectives even though he could not see either of them. On pit signals alone he had to get away from Brabham and at the same time catch up the ailing BRM.

Arundell got himself onto the podium with 3rd place

Motorsport Images

Not long after Hill’s trouble began the other BRM was also affected, and Ginther disappeared altogether for his engine cut out for the same reason and would not cut in again. It stopped out on the fast swerves on the back of the circuit and Ginther was able to watch how Clark gained valuable yards over his rivals. When the pump and pipes had cooled off he started up and joined in the race again, much to the surprise of his pit, for he went by as if nothing had happened! However, next lap the trouble recurred, so he stopped at the pits and had water poured over the pump; this effected a cure but it was obviously only going to be a matter of time before the temperature rose to vaporising point once more.

Bandini was also having injection trouble, for his V8 Ferrari was still running badly and finally stopped altogether. On lap 33 Phil Hill came into the pits to see if all was well with the back suspension, for the car felt peculiar and he was sure something had broken. Nothing could be found wrong so he went on again, and a few laps later Bonnier came into his pit with the same complaint, but all was well with the Brabham-BRM so he rejoined the race.

It was most likely a change in the direction of the wind that caused these two drivers to think something was wrong, for the wind blows between the sand dunes in some peculiar ways, and after the race Clark said he had noticed a change in the handling of the Lotus about half-way through the race. On one particular corner the car had been sliding across to the edge of the road and it suddenly stopped doing this, presumably because the wind had changed direction and he was sliding into a strong side wind.

At half distance, or 40 laps, the Lotus was about 29sec ahead of the V8 Ferrari, and the sick BRM of Graham Hill was a further 31sec behind. Then came Arundell and Brabham still on the same lap as Clark, but all the others had been lapped, their order being McLaren, Amon, Bonnier, Anderson and Hailwood, the last two having a good race together though both suffering a handicap. Anderson had petrol spraying into his face from an overflow, and Hailwood was having to be careful as his car had had to be repaired with a used crown-wheel and pinion and there was no guarantee that it would last the race.

“Anderson had petrol spraying into his face from an overflow”

Just as Brabham had got his sights on Arundell his engine died and he coasted into his pit, the drive to the ignition distributor having sheared, so the second Brabham car was out. Clark was way out on his own, drawing away from Surtees all the time and regularly lapping the tail-enders and the mid-field runners. Baghetti and Siffert were having a little private motor race of their own, even though they were not on the same lap, and were right at the back of the field.

On lap 47 Arundell passed the ailing BRM of Graham Hill, who by this time was getting accustomed to the violent jerks as his engine went “off” and “on” and was bracing himself out of the seat for the jerking was beginning to hurt his back. What it was doing to the gearbox and the drive-shafts hardly bears thinking about and says a lot for the robust design of the BRM. On lap 49 Clark lapped Hill and after one more lap of this suffering the BRM driver decided to stop at his pit. This time they were ready with a remedy and had a large fuel funnel and water ready, so as soon as Hill stopped they stuffed the neck of the funnel into the cockpit and poured water over the pump. The cockpit was swilling in water when Hill accelerated away and, as he said afterwards, the surge of water cooled his ardour as well as the pump!

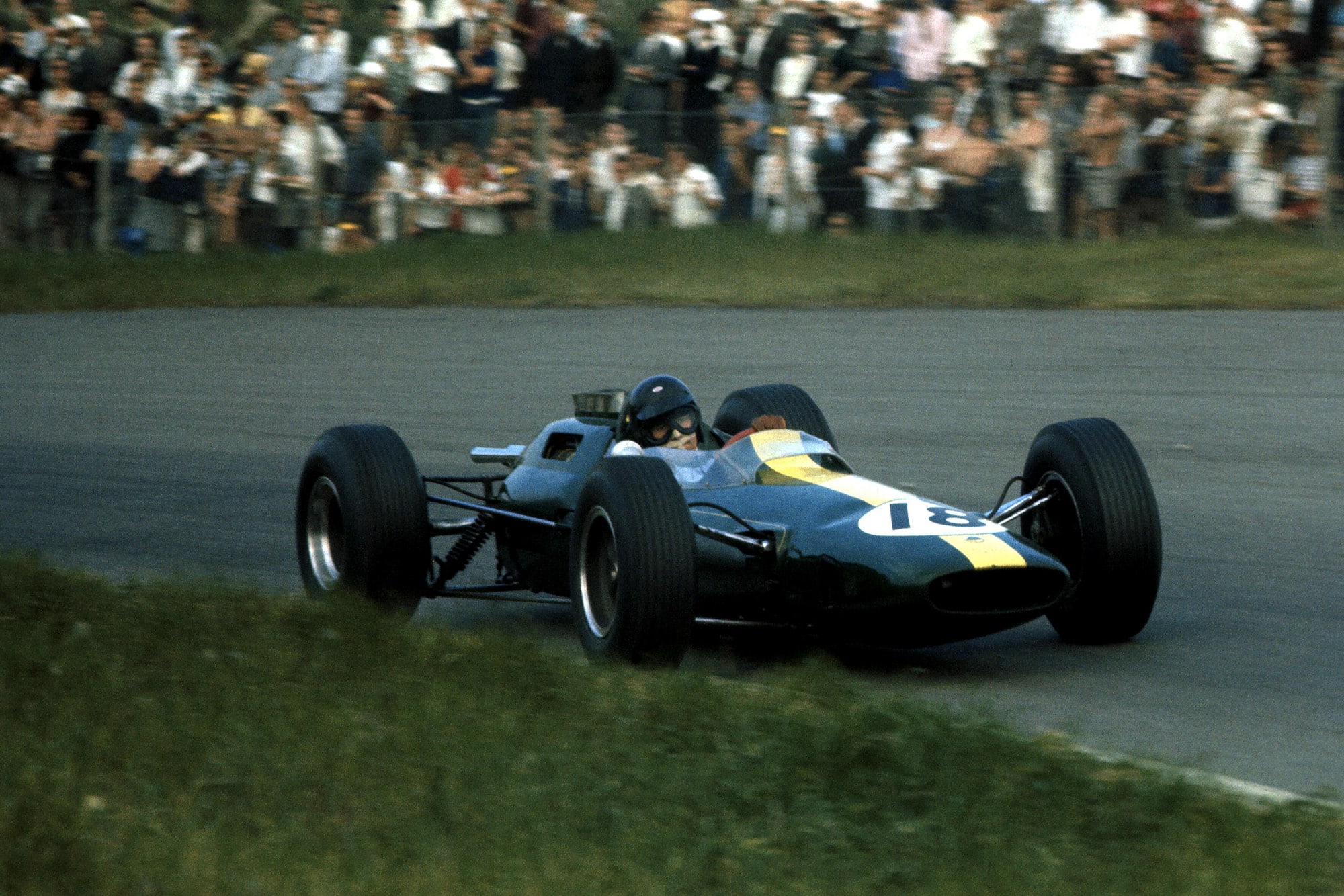

Clark lapped all but one the rest of the field on his way to victory

Motorsport Images

On lap 51 Clark lapped Arundell, who was now in third place, and the number two driver moved neatly to one side to let his leader through, and by lap 55 his lead over Surtees was 45sec, and at that he settled down, lapping in 1min 37sec or more Graham Hill had rejoined the race in sixth place and, now cool, the fuel system was working properly and the BRM was going as well as it had at the start of the race. It did not take him long to catch McLaren and Amon and it looked as though he might catch Arundell, but then the pump overheated again and he was back to erratic running.

Ginther was suffering the same trouble once more and made another pit stop for more water cooling, while Hailwood had to give up altogether when his crown-wheel and pinion gave out. Amon got past McLaren, the Parnell Lotus-BRM going very well, and the young New Zealander was having a good go. McLaren was far from happy and was gradually being worn down by the inferior handling of his Cooper, and now Anderson began to close up on him.

Although Surtees was securely in second place he was far from confident, for the Ferrari was giving indications of trouble in the engine compartment, and he was glad that the third-place man was not close enough to worry him. Team Lotus had urged Arundell on once more when it looked as though Graham Hill might catch him, and he had immediately speeded up, but was now settled in third place, which was very creditable as the two in front of him were Clark and Surtees.

Clark reeled off the closing laps with clockwork-like precision, a joy to behold and a lesson to all, and led Surtees home by 53.6sec, everyone else being a lap or more behind. With only four laps to go Anderson got past McLaren and got himself a very worthy sixth place, and the rest of the twelve finishers straggled home.